Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

The Passing of the Fur Lords

When Astoria passed to the Nor'westers, with it

came, as we shall see, an opportunity of acquiring for Great Britain

the whole of the vast region west of the Rockies, including

California and Alaska. Gray's feat in finding the mouth of the

Columbia, and the explorations of Lewis and Clark overland to the

same river, gave the United States possession of a part of this

territory by right of discovery; but this possession was practically

superseded by the transfer of Astor's fort to the British Canadian

Company. Yet, today, we find Britain not in possession of

California, not in possession of the region round the mouth of the

Columbia, not in possession of Alaska. The reason for this will

appear presently.

The Treaty of Ghent which closed the War of 1812 made no mention of

the boundaries of Oregon, but it provided that any territory

captured by either nation in the course of the war should be

restored to the original owner. The question then arose: did this

clause in the treaty apply to Astoria? Was the taking over of the

fur post by the British company in reality an act of war? The United

States said Yes; Great Britain said No; and both nations claimed

sovereignty over Oregon. In 1818 a provisional agreement was

reached, under which either nation might trade and establish

settlements in the disputed territory. But it was now utterly

impossible for Astor to prosecute the fur trade on the Pacific. The

'Bostonnais' had lost prestige with the Indians when the Tonquin

sank off Clayoquot, and the more experienced British and Canadian

traders were in control of the field. At this time the Hudson's Bay

Company and the Nor'westers were waging the trade war that

terminated in their union in 18201821; and when the united companies

came to assign officers to the different districts, John M'Loughlin,

who had been a partner in the North West Company, was sent overland

to rule Oregon.

What did Oregon comprise? At that time no man knew; but within ten

years after his arrival in 1824 M'Loughlin had sent out hunting

brigades, consisting of two or three hundred horsemen, in all

directions: east, under

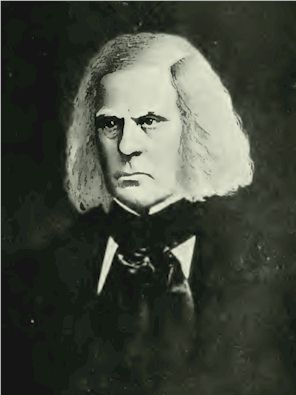

John M'loughlin

Photographed by Savannah from an original painting

Alexander Ross, as far as Montana and Idaho; south, under Peter

Skene Ogden, as far as Utah and Nevada and California; along the coast south as

far as Monterey, under Tom Mackay, whose father had been murdered on the Tonquin

and whose widowed mother had married M'Loughlin; north, through New Caledonia,

under James Douglas - 'Black Douglas ' they called the dignified, swarthy young

Scotsman who later held supreme rule on the North Pacific as Sir James Douglas,

the first governor of British Columbia. If one were to take a map of

M'Loughlin's transmontane empire and lay it across the face of a map of Europe,

it would cover the continent from St Petersburg to Madrid.

The ruler of this vast domain was one of the noblest men in the annals of the

fur trade. John M'Loughlin was a Canadian, born at Riviere du Loup, and he had

studied medicine in Edinburgh. The Indians called him 'White Eagle,' from his

long, snow white hair and aquiline features. When M'Loughlin reached Oregon - by

canoe two thousand miles to the Rockies, by packhorse and canoe another seven

hundred miles south to the Columbia - two of the first things he saw were that

Astoria, or Fort George, was too near the rum of trading schooners for the

wellbeing of the Indians, and that it would be quite possible to raise food for

his men on the spot, instead of transporting it over two watersheds and across

the width of a continent. He at once moved the headquarters of the company from

Astoria to a point on the north bank of the Columbia near the Willamette, where

he erected Fort Vancouver. Then he sent his men overland to the Spaniards of

Lower California to purchase seed wheat and stock to begin farming in Oregon in

order to provision the company's posts and brigades. It was about the time that

his wheat fields and orchards began to yield that some passing ocean traveler

asked him: 'Do you think this country will ever be settled? ' 'Sir,' answered

M'Loughlin, emphasizing his words by thumping his gold headed cane on the floor,

'wherever wheat grows, men will go, and colonies will grow.' Afterwards, when he

had to choose between loyalty to his company and saving the lives of thousands

of American settlers who had come over the mountains destitute, these words of

his were quoted against him. He had, according to the directors of the company,

favored settlement rather than the fur trade.

Fort Vancouver

From a print in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library

Meanwhile, M'Loughlin ruled in a sort of rude baronial splendor

on the banks of the Columbia. The 'Big House,' as the Indians always called the

governor's mansion, stood in the centre of a spacious courtyard surrounded by

palisades twenty feet high, with huge brass padlocks on the entrance gates.

Directly in front of the house two cannon were stationed, and piled up behind

them ready for instant use were two pyramids of balls. Only officers of some

rank dined in the Hall; and if visitors were present from coastal ships that

ascended the river, Highland kilties stood behind the governor's chair playing

the bagpipes. Towards autumn the southern and eastern brigades set out on their

annual hunt in California, Nevada, Montana, and Idaho. Towards spring, when the

upper rivers had cleared of ice, the northern brigades set out for the interior

of New Caledonia. Nothing more picturesque was ever seen in the fur trade than

these Oregon brigades. French Canadian hunters with their Indian wives would be

gathered to the number of two hundred. Indian ponies fattened during the summer

on the deep pasturage of the Willamette or the plains of Walla Walla would be

brought in to the fort and furbished forth in gayest of trappings. Provisions

would then be packed on their backs. An eager crowd of wives and sweethearts and

children would dash out for a last goodbye. The governor would personally shake

hands with every departing hunter. Then to bugle call the riders mounted their

restive ponies, and the captain - Tom Mackay or Ogden or Ross - would lead the

winding cavalcade into the defiles of mountain and forest, whence perhaps they

would not emerge for a year and a half. Though the brigades numbered as many as

two hundred men, they had to depend for food on the rifles of the hunters,

except for flour and tobacco and bacon supplied at the fort. Once the brigade

passed out of sight of the fort, the hunters usually dashed ahead to anticipate

the stampeding of game by the long, noisy, slow moving line. Next to the hunters

would come the old bell mare, her bell tinkling through the lonely silences. Far

in the rear came the squaws and trappers. Going south, the aim was to reach the

traverse of the deserts during winter, so that snow would be available for

water. Going east, the aim was to cross the mountain passes before snowfall.

Going north, the canoes must ascend the upper rivers before ice formed. But

times without number trappers and hunters were caught in the desert without snow

for water; or were blocked in the mountain passes by blizzards; or were wrecked

by the ice cutting their canoes on the upper rivers. Innumerable place names

commemorate the presence of humble trapper and hunter coursing the wilderness in

the Oregon brigades. For example: Sublette's River, Payette's River, John Day's

River, the Des Chutes, and many others. Indeed, many of the place names

commemorate the deaths of lonely hunters in the desert. Crow and Blackfoot and

Sioux Indians often raided the brigades when on the home trip loaded with

peltry. One can readily believe that rival traders from the Missouri instigated

some of these raids. There were years when, of two hundred hunters setting out,

only forty or fifty returned; there were years when the Hudson's Bay brigades

found snowbound, stormbound, starving American hunters, and as a price for food

exacted every peltry in the packs; and there were years when rival American

traders bribed every man in Ogden's brigade to desert.

The New Caledonia brigades set out by canoe - huge, long, cedar

lined craft manned by fifty or even ninety men. These brigades were decked out

gayest of all. Flags flew at the prow of each craft. Voyageurs adorned

themselves with colored sashes and headbands, with tinkling bells attached to

the buckskin fringe of trouser leg. Where the rivers narrowed to dark and

shadowy canyons, the bagpipes would skirl out some Highland air, or the French

voyageurs would strike up some song of the habitant, paddling and chanting in

perfect rhythm, and sometimes beating time with their paddles on the gunwales.

Leaders of the canoe brigades understood well the art of never permitting fear

to enter the souls of their voyageurs. Where the route might be exposed to

Indian raid, a regale of rum would be dealt out; and the captain would keep the

men paddling so hard there was no time for thought of danger.

In course of time the northern brigades no longer attempted to

ascend the entire way to the interior of New Caledonia by boat. Boats and canoes

would be left on the Columbia at Fort Colville or at Fort Okanagan (both south

of the present international boundary), and the rest of the trail would be

pursued by pack horse. Kamloops became the great halfway house of these

northbound brigades; and horses were left there to pasture on the high, dry

plains, while fresh horses were taken to ascend the mountain trails. Fort St

James on Stuart Lake became the chief post of New Caledonia. Here ruled young

James Douglas, who had married the daughter of the chief factor William

Connolly. Ordinarily, the fort on the blue alpine lake lay asleep like an August

day; but on the occasion of a visit by the governor or the approach of a

brigade, the drowsy post became a thing of life. Boom of cannon, firing of

rifles, and skirling of bagpipes welcomed the long cavalcade. The captain of the

brigade as he entered the fort usually wore a high and pompous beaver hat, a

velvet cloak lined with red silk, and knee breeches with elaborate Spanish

embossed leather leggings. All this show was, of course, for the purpose of

impressing the Indians. Whether impressed or not, the Indians always counted the

days to the wild riot of feasting and boat races and dog races and horse races

that marked the arrival or departure of a brigade. New Caledonia, as we know, is

now a part of Canada; but why does not the Union Jack float over the great

region beyond the Rockies to the south - south of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and

the 49th parallel? Over all this territory British fur lords once held sway.

California was in the limp fingers of Mexico, but the British traders were

operating there, and had ample opportunity to secure it by purchase long before

it passed to the United States in 1848. Sir George Simpson, the resident

governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, advised the company to purchase it, but

the directors in London could not see furs in the suggestion. Simpson would have

gone further, and reached out the company's long arm to the islands of the

Pacific and negotiated with the natives for permission to build a fort in

Hawaii. James Douglas was for buying all Alaska from the Russians; but to the

directors of the Hudson's Bay Company Alaska seemed as remote and as worthless

as Siberia, so they contented themselves with leasing a narrow strip along the

shore. Thus California, Alaska, and Hawaii might easily have become British

territory; but the opportunity was lost, and they went to the United States. So,

too, did the fine territory of Oregon, out of which three states were afterwards

added to the American Union. But the history of Oregon is confused in a maze of

politics, into which we cannot enter here. As we have seen, Bruno Heceta, acting

for Spain, was the first mariner to sight the Columbia, and the American, Robert

Gray, was the first to enter its mouth, thus proving Heceta's conjecture of a

great river. Then for Great Britain came Vancouver and Broughton; then the

Americans, Lewis and Clark and the Astorians; and finally Thompson, the British

Nor'westers and the first man to explore the great river from its source to the

sea. Then during the War of 18 12 the American post on the Columbia passed to

the North West Company of Montreal; and if it had not been for the 'joint

occupancy' agreement between Great Britain and the United States in 1818, Oregon

would undoubtedly have remained British. But with the 'joint occupancy '

arrangement leaving sovereignty in dispute, M'Loughlin of Oregon knew well that

in the end sovereignty would be established, as always, by settlement.

First came Jedediah Smith, the American fur trader, overland. He was robbed to

the shirt on his back by Indians at the Umpqua River. There and then came the

great choice to M'Loughlin - should he save the life of rivals, or leave them to

be murdered by Indians? He sent Tom Mackay to the Umpqua, punished the robber

Indians, secured the pilfered furs, and paid the American for them. Then came

American missionaries overland - the Lees and Whitman. Then came Wyeth, the

trader and colonizer from Boston. The company fought Wyeth's trade and bought

him out; but when the turbulent Indians crowded round the 'White Eagle,' chief

of Fort Vancouver, asking, 'Shall we kill- shall we kill the 'Bostonnais'? '

M'Loughlin struck the chief plotter down, drove the others from the fort, and

had it noised about among the tribes that if any one struck the white '

Bostonnais,' M'Loughlin would strike him. At the same time, M'Loughlin earnestly

desired that the territory should remain British. In 1838, at a council of the

directors in London, he personally urged the sending of a garrison of British

soldiers, and that the government should take control of Oregon in order to

establish British rights. His suggestions received little consideration. Had not

the company singlehanded held all Rupert's Land for almost two hundred years?

Had they not triumphed over all rivals? They would do so here. But by 1843

immigrants were pouring over the mountains by the thousands. Washington living's

Astoria and Captain Bonneville and the political cry of 'Fifty-four forty or

fight ' - which meant American possession of all south of Alaska - had roused

the attention of the people of the United States to the merits of Oregon, and

caused them to make extravagant claims. Long before the Oregon Treaty of 1846,

which established the 49th parallel as the boundary, M'Loughlin had foreseen

what was coming. The movement from the east had become a tide. The immigrants

who came over the Oregon Trail in 1843 were starving, almost naked, and without

a roof. Again the Indians crowded about M'Loughlin. 'Shall we kill? Shall we

kill? 'they asked. M'Loughlin took the rough American overlanders into his fort,

fed them, advanced them provisions on credit, and sent them to settle on the

Willamette. Some of them showed their ingratitude later by denouncing M'Loughlin

as 'an aristocrat and a tyrant.' The settlers established a provisional

government in 1844, and joined in the rallying cry of ' Fifty-four forty or

fight.' This, as M'Loughlin well knew, was the beginning of the end. His friends

among the colonists begged him to subscribe to the provisional government in

order that they might protect his fort from some of their number who threatened

to 'burn it about his ears.' He had appealed to the British government for

protection, but no answer had come; and at length, after a hard struggle and

many misgivings, he cast in his lot with the Americans. Two years later, in

1846, he retired from the service of the company and went to live among the

settlers. He died at Oregon City on the Willamette in 1857.

As early as June 1842 M'Loughlin had sent Douglas prospecting in Vancouver

Island, which was north of the immediate zone of dispute, for a site on which to

erect a new post. The Indian village of Camosun, the Cordoba of the old Spanish

charts, stood on the site of the present city of Victoria. Here was fresh water;

here was a good harbor; here was shelter from outside gales. Across the sea lay

islands ever green in a climate always mild and salubrious. Fifteen men left old

Fort Vancouver with Douglas in March 1843 in the company's ship the Beaver y and

anchored at Vancouver Island, just outside Camosun Bay. With Douglas went the

Jesuit missionary, Father Bolduc, who on March 19 celebrated the first Mass ever

said on Vancouver Island, and afterwards baptized Indians till he was fairly

exhausted. In three days Douglas had a well dug and timbers squared. For every

forty pickets erected by the Indians he gave them a blanket. By September

stockades and houses had been completed, and as many as fifty men had come to

live at the new fort, to which the name Victoria was finally given. Victoria

became the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company on the Pacific. It was

unique as a fortified post, in that it was built without the driving of a single

nail, wooden pegs being used instead.

By 1849 the discovery of gold in California was bringing a rush of overlanders.

There had been rumors of the discovery of precious metals on the Fraser and in

East Kootenay. The company became alarmed; and Sir John Pelly, the governor in

England, and Sir George Simpson, the governor in America, went to the British

government with the disquieting question: What is to hinder American colonists

rolling north of the boundary and establishing right of possession there as they

did on the Columbia? By no stretch of its charter could the Hudson's Bay Company

claim feudal rights west of the Rockies. What, my Lord Grey asks, would the

company advise the British government to do to avert this danger from a tide of

democracy rolling north? Why, of course, answers Sir John Pelly, proclaim

Vancouver Island a British colony and give the company a grant of the territory

and the company will colonize it with British subjects. The proposal was laid

before parliament. It would be of no profit to follow the debate that ensued in

the House of Commons, which was chiefly ' words without knowledge darkening

counsel.' The request was officially granted in January 1849; and Richard

Blanshard, a barrister of London, was dispatched as governor of the new colony.

But as he had neither salary nor subjects, he went back to England in disgust in

1851, and James Douglas of the Hudson's Bay Company reigned in his stead.

But fate again played the unexpected part, and rang down the curtain on the fur

lords of the Pacific coast. A few years previously Douglas had seen M'Loughlin

compelled to choose between loyalty to his company and loyalty to humanity. A

choice between his country and his company was now unexpectedly thrust on the

reticent, careful, masterful Douglas. In 1856 gold was discovered in the form of

large nuggets on the Fraser and the Thompson, and adventurers poured into the

country - 20,000 in a single year. Douglas foresaw that this meant British

Empire on the Pacific and that the supremacy of the fur traders was about to

pass away. The British government bought back Vancouver Island, and proclaimed

the new colony of British Columbia on the mainland. Douglas retired from the

company's service and was appointed governor of both colonies. In 1866 they were

united under one government.

The stampede of treasure seekers up the Fraser is another story.

When the new colony on the mainland came into being, and the Hudson's Bay

Company fell from the rank of a feudal overlord to that of a private trader, the

pioneer days of the Pacific became a thing of the past.

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

Pioneers of the Pacific Coast, A Chronicle Of Sea

Rovers And Fur Hunters, By Agnes C. Laut, Toronto. Glasgow, Brook &

Company, 1915

Chronicles of Canada |