Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

Wintering on the Bay

Little is known of the many strange things which

must have taken place on the voyage. On board the Edward and Ann

sickness was prevalent and the ship's surgeon was kept busy. There

were few days on which the passengers could come from below - decks.

When weather permitted, Captain Macdonell, who knew the dangers to

be encountered in the country they were going to, attempted to give

the emigrants military drill. ' There never was a more awkward

squad,' was his opinion,' not a man, or even officer, of the party

knew how to put a gun to his eye or had ever fired a shot.' A

prominent figure on the Edward and Ann was a careless-hearted

cleric, whose wit and banter were in evidence throughout the voyage.

This was the Reverend Father Burke, an Irish priest. He had stolen

away without the leave of his bishop, and it appears that he and

Macdonell, although of the same faith, were not the best of friends.

After a stormy voyage of nearly two months the ships entered the

long, barren straits leading into Hudson Bay. From the beginning of

September the fleet had been hourly expected at York Factory, and

speculation was rife there as to its delay in arriving. On September

24 the suspense ended, for the look-out at the fort descried the

ships moving in from the north and east. They anchored in the

shallow haven on the western shore, where two streams, the Nelson

and the Hayes, enter Hudson Bay, and the sorely tried passengers

disembarked. They were at once marched to York Factory, on the north

bank of the Hayes. The strong palisades and wooden bastions of the

fort warned the newcomers that there were dangers in America to be

guarded against. A pack of 'husky' dogs came bounding forth to meet

them as they approached the gates.

A survey of the company's buildings convinced Macdonell that much

more roomy quarters would be required for the approaching winter,

and he determined to erect suit-able habitations for his people

before snowfall. With this in view he crossed over to the Nelson and

ascended it until he reached a high clearing on its left bank, near

which grew an abundance of white spruce. He brought up a body of

men, most of whom now received their first lesson in woodcraft. The

pale and flaky-barked aromatic spruce trees were felled and stripped

of their branches. Next, the logs were 'snaked ' into the open,

where the dwellings were to be erected, and hewed into proper shape.

These timbers were then deftly fitted together and the four walls of

a rude but substantial building began to rise. A drooping roof was

added, the chinks were closed, and then the structure was complete.

When a sufficient number of such houses had been built, Macdonell

set the party to work cutting firewood and gathering it into

convenient piles.

The prudence of these measures became apparent when the frost king

fixed his iron grip upon land and sea. As the days shortened, the

rivers were locked deep and fast; a sharp wind penetrated the

forest, and the salty bay was fringed with jagged and glistening

hum-mocks of ice. So severe was the cold that the newcomers were

loath to go forth from their warm shelter even to haul food from the

fort over the brittle, yielding snow. Under such conditions life in

the camp grew monotonous and dull. More serious still, the food they

had to eat was the common fare of such isolated winterers; it was

chiefly salt meat. The effect of this was seen as early as December.

Some of the party became listless and sluggish, their faces turned

sallow and their eyes appeared sunken. They found it difficult to

breathe and their gums were swollen and spongy. Macdonell, a veteran

in hardship, saw at once that scurvy had broken out among them; but

he had a simple remedy and the supply was without limit. The sap of

the white spruce was extracted and administered to the sufferers.

Almost immediately their health showed improvement, and soon all

were on the road to recovery. But the medicine was not pleasant to

take, and some of the party at first foolishly refused to submit to

the treatment.

The settlers, almost unwittingly, banded together into distinct

groups, each individual tending to associate with the others from

his own home district. As time went on these groups, with their

separate grievances, gave Macdonell much trouble. The Orkneymen, who

were largely servants of the Hudson's Bay Company, were not long in

incurring his disfavor. To him they seemed to have the appetites of

a pack of hungry wolves. He dubbed them 'lazy, spiritless and

ill-disposed.' The 'Glasgow rascals,' too, were a source of

annoyance.' A more . . . cross-grained lot,' he asserted, 'were

never put under any person's care.'

Owing to the discord existing in the camp, the New Year was not

ushered in happily. In Scotland, of all the days of the year, this

anniversary was held in the highest regard. It was generally

celebrated to the strains of 'Weel may we a' be,' and with effusive

hand-shakings, much dining, and a hot kettle. The lads from the

Orkneys were quite wide awake to the occasion and had no intention

of omitting the customs of their sires. On New Year's Day they were

having a rollicking time in one of the cabins. But their enthusiasm

was quickly damped by a party of Irish who, having primed their

courage with whisky, set upon the merry-makers and created a scene

of wild disorder. In the heat of the melee three of the Orkneymen

were badly beaten, and for a month their lives hung in the balance.

Captain Macdonell later sent several of the Irish back to Great

Britain, saying that such 'worthless blackguards' were better under

the discipline of the army or the navy.

One of the number who had not taken kindly to Miles Macdonell as a

'medicine-man' was William Findlay, a very obdurate Orkneymen, who

had flatly refused to soil his lips with the wonder-working syrup of

the white spruce. Shortly afterwards, having been told to do

something, he was again disobedient. This time he was forced to

appear before Magistrate Hillier of the Hudson's Bay Company and was

condemned to gaol. As there was really no such place, a log-house

was built for Findlay, and he was imprisoned in it. A gruff-noted

babel of dissent arose among his kinsfolk, supported by the men from

Glasgow. A gang of thirteen, in which both parties were represented,

put a match to the prison where Findlay was confined, and rescued

its solitary inmate out of the blaze. Then, uttering defiance, they

seized another building, and decided to live apart. Thus, with the

attitude of rebels and well supplied with firearms, they kept the

rest of the camp in a state of nervousness for several months. In

June, however, these rebels allowed them-selves to fall into a trap.

Having crossed the Nelson, they found their return cut off by the

melting of the ice. This put them at

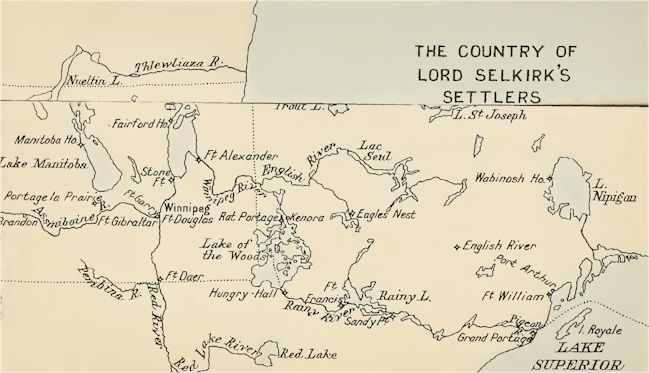

The Country of Lord Selkirk's Settlers

the mercy of the officials at York Factory, and they were forced to surrender.

After receiving their humble acknowledgments Macdonell v/as not disposed to

treat them severely, and he took them back into service.

But what of jovial Father Burke since his arrival on the shores of Hudson Bay?

To all appearances, he had not been able to restrain his flock from mischief. He

had, however, been exploring on his own account, and thoroughly believed that he

had made some valuable discoveries. He had come upon pebbles of various kinds

which he thought were precious stones. Some of them shone like diamonds; others

seemed like rubies. Father Burke was indeed sure that bits of the sand which he

had collected contained particles of gold. Macdonell himself believed that the

soil along the Nelson abounded in mineral wealth. He told the priest to keep the

discovery a secret, and sent samples of sand and stone to Lord Selkirk, advising

him to acquire the banks of the Nelson River from the company. In the end, to

the disgust of Macdonell and Father Burke, not one sample proved of any value.

Weeks before the ice had left the river; the colonists became impatient to set

forward on the remainder of their journey. To transport so many persons, with

all their belongings and with sufficient provisions, seven or eight hundred

miles inland was an undertaking formidable enough to put Captain Macdonell's

energies to the fullest test. The only craft available were bark canoes, and

these would be too fragile for the heavy cargoes that must be borne. Stouter

boats must be built. Macdonell devised a sort of punt or flat-bottomed boat,

such as he had formerly seen in the colony of New York. Four of these clumsy

craft were constructed, but only with great difficulty, and after much trouble

with the workmen. Inefficiency, as well as mis-conduct, on the part of the

colonists was a sore trial to Macdonell. The men from the Hebrides were now

practically the only members of the party who were not, for one reason or

another, in his black book.

It was almost midsummer before the boats began to push up the Hayes River for

the interior. There were many blistered hands at the oars; nevertheless, on the

journey they managed to make an average of thirteen miles each day. Before the

colonists could reach Oxford House, the next post of the Hudson's Bay Company,

three dozen portages had to be passed. It was with thankful hearts that they

came to Holy Lake and caught sight of the trading-post by its margin. Here was

an ample reach of water, reminding the Highlanders of a loch of far-away

Scotland. When the wind died down, Holy Lake was like a giant mirror. Looking

into its quiet waters, the voyagers saw great fish swimming swiftly. From Oxford

House the route lay over a height-of-land to the head-waters of the Nelson.

After a series of difficulties the party reached Norway House, another post of

the Hudson's Bay Company, on an upper arm of Lake Winnipeg. At this time Norway

House was the centre of the great fur-bearing region. The colonists found it

strongly en-trenched in a rocky basin and astir with life. After a short rest

they proceeded towards Lake Winnipeg, and soon were moving slowly down its

low-lying eastern shore. Here they had their first glimpse of the prairie

country, with its green carpet of grass. Out from the water's edge grew tall,

lank reeds, the lurking place of snipe and sand-piper. Doubtless, in the brief

night-watches, they listened to the shrill cry of the restless lynx, or heard

the yapping howl of the timber wolf as he slunk away among the copses. But

presently the boats were gliding in through the sand-choked outlet of the Red

River, and they were on the last stage of their journey.

Some forty miles up-stream from its mouth the Red River bends

sharply towards the east, forming what is known as Point Douglas in the present

city of Winnipeg. Having toiled round this point, the colonists pushed their

boats to the muddy shore. The day they landed, the natal day of a community

which was to grow into three great provinces of Canada, was August 30, 1812.

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

The Red River Colony, A Chronicle of the

Beginnings of Manitoba, By Louis Aubrey Wood, Toronto, Glasgow,

Brook & Company 1915

Chronicles of Canada |