Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

Purse Strings Loosen

Traffic in furs was hazardous, but it brought great

returns. The peltry of the north, no less than the gold and silver

of the south, gave impetus to the efforts of those who first settled

the western hemisphere. In expectation of ample profits, the fur

ship threaded its way through the ice-pack of the northern seas, and

the trader sent his canoes by tortuous stream and toilsome portage.

In the early days of the eighteenth century sixteen beaver skins

could be obtained from the Indians for a single musket, and ten

skins for a blanket. Profits were great, and with the margin of gain

so enormous, jealousies and quarrels without number were certain to

arise between rival fur traders.

The right to the fur trade in America had been granted, given away,

as the English of the time thought, by the hand of Charles II of

England. In prodigal fashion Charles conceded, in 1670, a charter,

which conveyed

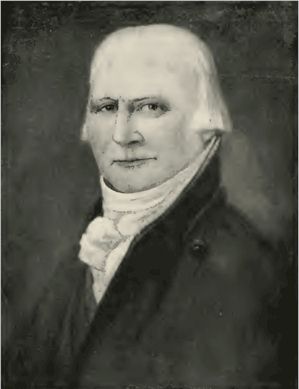

Joseph Frobisher

A Partner In The North-West Company

From the John Russ Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library

extensive lands, with the privileges of monopoly, to the

'Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson's Bay.' But if the

courtiers of the Merry Monarch had any notion that he could thus exclude all

others from the field, their dream was an empty one. England had an active rival

in France, and French traders penetrated into the region granted to the Hudson's

Bay Company. Towards the close of the seventeenth century Le Moyne d' Iberville

was making conquests on Hudson Bay for the French king, and Greysolon Du Lhut

was carrying on successful trading operations in the vicinity of Lakes Nipigon

and Superior. Even after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) had given the Hudson Bay

territories to the English, the French-Canadian explorer La Verendrye entered

the forbidden lands, and penetrated to the more remote west. A new situation

arose after the British conquest of Canada during the Seven Years' War. Plucky

independent traders, mostly of Scottish birth, now began to follow the

watercourses which led from the rapids of Lachine on the St Lawrence to the

country beyond Lake Superior. These men treated with disdain the royal charter

of the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1783 a group of them united to form the North-

West Company, with headquarters at Montreal. The organization grew in strength

and became the most power-ful antagonist of the older company, and the open feud

between the two spread through the wide region from the Great Lakes to the

slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

The Nor'westers, as the partners and servants of the North-West Company were

called, were bold competitors. Their enthusiasm for the conflict was all the

more eager because their trade was regarded as illicit by their rivals. There

was singleness of purpose in their ranks; almost every man in the service had

been tried and proved. All the Montreal partners of the company had taken the

long trip to the Grand Portage, a transit station at the mouth of the Pigeon

River, on the western shore of Lake Superior. Other partners had wintered on the

frozen plains or in the thick of the forest, tracking the yellow-grey badger,

the pine-marten, and the greedy wolverine. The guides employed by the company

knew every mile of the rivers, and they rarely mistook the most elusive trail.

Its interpreters could converse with the red men like natives. . Even the clerks

who looked after the office routine of the company labored with zest, for, if

they were faithful and attentive in their work, the time would come when they,

too, would be elected as partners in the great concern. The canoe men were

mainly French Canadian coureurs de bois, gay voyageurs on lake and stream. In

the veins of many of them flowed the blood of Cree or Iroquois. Though half

barbarous in their mode of life, they had their own devotions. At the first

halting-place on their westward journey, above Lachine, they were accustomed to

enter a little chapel which stood on the bank of the Ottawa. Here they prayed

reverently that 'the good Saint Anne,' the friend of all canoe men, would guard

them on their way to the Grand Portage. Then they dropped an offering at Saint

Anne's shrine, and pointed their craft against the current. These rovers of the

wilderness were buoyant of heart, and they lightened the weary hours of their

six weeks' journey with blithe songs of love and the river. When the snow fell

and ice closed the river, they would tie their 'husky ' dogs to sledges and

travel over the desolate wastes, carrying furs and provisions. It was a very

different company that traded into Hudson Bay. The Hudson's Bay Company was

launched on its career in a princely manner, and had tried to cling fast to its

time-worn traditions. The bundles of uncured skins were received from the red

men by its servants with pomp and dignity. At first the Indians had to bring

their 'catch ' to the shores of Hudson Bay itself, and here they were made to

feel that it was a privilege to be allowed to trade with the company. Some-times

they were permitted to pass in their wares only through a window in the outer

part of the fort. A beaver skin was the regular standard of value, and in return

for their skins the savages received all manner of gaudy trinkets and also

useful merchandise, chiefly knives, hatchets, guns, ammunition, and blankets.

But before the end of the eighteenth century the activity of the Nor'westers had

forced the Hudson's Bay Company out of its aristocratic slothfulness. The

savages were now sought out in their prairie homes, and the company began to set

up trading-posts in the interior, all the way from Rainy Lake to Edmonton House

on the North Saskatchewan.

Such was the situation of affairs in the fur-bearing country

when the Earl of Selkirk had his vision of a rich prairie home for the desolate

Highlanders. Though he had not himself visited the Far West, he had some

conception of the probable outcome of the fierce rivalry between the two great

fur companies in North America. He foresaw that, sooner or later, if his scheme

of planting a colony in the interior was to prosper, he must ally him-self with

one or the other of these two factions of traders.

We may gain a knowledge of Lord Selkirk's ideas at this time from his own

writings and public utterances. In 1 805 he issued a work on the Highlands of

Scotland, which Sir Walter Scott praised for its ' precision and accuracy,' and

which expressed the significant sentiment that the government should adopt a

policy that would keep the Highlanders within the British Empire. In 1806, when

he had been chosen as one of the sixteen representative peers from Scotland, he

delivered a speech in the House of Lords upon the subject of national defense,

and his views were after-wards stated more fully in a book. With telling logic

he argued for the need of a local militia, rather than a volunteer force, as the

best protection for England in a moment of peril. The tenor of this and

Selkirk's other writings would indicate the staunchness of his patriotism. In

his efforts at colonization his desire was to keep Britain's sons from

emigrating to an alien shore.

'Now, it is our duty to befriend this people,' he affirmed, in writing of the

Highlanders. 'Let us direct their emigration; let them be led abroad to new

possessions.' Selkirk states plainly his reason. 'Give them homes under our own

flag,' is his entreaty, 'and they will strengthen the empire.'

In 1807 Selkirk was chosen as lord-lieutenant of the stewartry of Kirkcudbright,

and in the same year took place his marriage with Jean Wedderburn-Colvile, the

only daughter of James Wedderburn-Colvile of Ochiltree. One year later he was

made a Fellow of the Royal Society, a distinction conferred only upon

intellectual workers whose labours have increased the world's stock of

knowledge.

After some shrewd thinking Lord Selkirk decided to throw in his lot with the

Hudson's Bay Company. Why he did this will subsequently appear. At first, one

might have judged the step unwise. The financiers of London believed that the

company was drifting into deep water. When the books were made up for 1808,

there were no funds avail-able for dividends, and bankruptcy seemed inevitable.

Anyone who owned a share of Hudson's Bay stock found that it had not earned him

a sixpence during that year. The company's business was being cut down by the

operations of its aggressive rival. The chief cause, however, of the company's

financial plight was not the trade war in America, but the European war, which

had dealt a heavy blow to British commerce. Napoleon had found himself unable to

land his army in England, but he had other means of striking. In 1806 he issued

the famous Berlin Decree, declaring that no other country should trade with his

greatest enemy. Dealers had been wont to come every year to London from Germany,

France, and Russia, in order to purchase the fine skins which the Hudson's Bay

Company could supply. Now that this trade was lost to the company, the profits

dis-appeared. For three seasons bale after bale of unsold peltry had been

stacked to the rafters of the London warehouse.

The Earl of Selkirk was a practical man; and, seeing the plight of the Hudson's

Bay Company, he was tempted to take advantage of the situation to further his

plans of emigration. Like a genuine lord of Galloway, however, he proceeded with

extreme caution. His initial move was to get the best possible legal advice

regarding the validity of the company's royal charter. Five of the foremost

lawyers in the land were asked for their opinion upon this matter. Chief of

those who were approached was Sir Samuel Romilly, the friend of Bentham and of

Mirabeau. The other four were George Holroyd and James Scarlet, both

distinguished pleaders, and William Cruise and John Bell. The finding of these

lawyers put the question out of doubt. The charter, they said, was flawless. Of

all the lands which were drained by the many rivers running into Hudson Bay, the

company was the sole proprietor. Within these limits it could appoint sheriffs

and bring law-breakers to trial. Besides, there was no-thing to prevent it from

granting to any one in fee-simple tracts of land in its vast domain. Having

satisfied himself that the charter of 1670 was legally unassailable, the earl

was now ready for his subsequent line of action. He had resolved to get a

foothold in the company itself. To affect this object he brought his own capital

into play, and sought at the same time the aid of his wife's relatives, the

Wedderburn-Colviles, and of other personal friends. Shares in the company had

depreciated in value, and the owners, in many cases, were jubilant at the chance

of getting them off their hands. Selkirk and his friends did not stop buying

until they had acquired about one-third of the company's total stock.

In the meantime the Nor'westers scented trouble ahead. As soon as Lord Selkirk

had /completed his purchase of Hudson's Bay /stock, he began to make overtures

to the company's shareholders to be allowed to plant a colony in the territories

assigned to I them by their royal charter. To the Nor'westers this proposition

was anathema. They; argued that if a permanent settlement was i established in

the fur country, the fur-bearing I animals would be driven out, and their trade

ruined. Their alarm grew apace. In May 1811 a general court of the Hudson's Bay

Company, which had been adjourned, was on the point of reassembling. The London

agents of the North-West Company decided to act at once. Forty-eight hours

before the general court opened three of their number bought up a quantity of

Hudson's Bay stock. One of these purchasers was the redoubtable explorer. Sir

Alexander Mackenzie.

Straightway there ensued one of the liveliest sessions that ever

occurred in a general court of the Hudson's Bay Company. The Nor'westers, who

now had a right to voice their opinions, fumed and haggled. Other share holders

flared into vigorous protest as the Earl of Selkirk's plan was disclosed. In the

midst of the clash of interests, however, the earl's following stated his

proposal succinctly. They said that Selkirk wished to secure a tract of fertile

territory within the borders of Rupert's Land, for purposes of colonization.

Preferably, this should lie in the region of the Red River, which ran northward

towards Hudson Bay. At his own expense Selkirk would people this tract within a

given period, foster the early efforts of its settlers, and appease the claims

of the Indian tribes that inhabited the territory. He promised, moreover, to

help to supply the Hudson's Bay Company with laborers for its work. " Had Lord

Selkirk been present to view the animated throng of merchant adventurers, he

would have foreseen his victory. In his first tilt with the Nor'westers he was

to be successful. The opposition was strong, but it wore down before the

onslaught of his friends. Then came the show of hands. There was no uncertainty

about the vote: two-thirds of the court had pledged themselves in favor of Lord

Selkirk's proposal.

By the terms of the grant which the general court made to Selkirk, he was to

receive 116,000 square miles of virgin soil in the locality which he had

selected. The boundaries of this immense area were carefully fixed. Roughly

speaking, it extended from Big Island, in Lake Winnipeg, to the parting of the

Red River from the head-waters of the Mississippi in the south, and from beyond

the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in the west to the shores of the

Lake of the Woods, and at one point almost to Lake Superior, in the east. If a

map is consulted, it will be seen that one-half of the grant lay in what is now

the province of Manitoba, the other half in the present states of Minnesota and

North Dakota.1

A great variety of opinions were expressed in London upon the subject of this

grant. Some wiseacres said that the earl's proposal was as extravagant as it was

visionary. One of Selkirk's acquaintances met him strolling along Pall Mall, and

brought him up short on the street with the query: 'If you are bent on doing

something futile, why do you not sow tares at home in order to reap wheat, or

plough the desert of Sahara, which is nearer? '

The extensive tract which the Hudson's Bay Company had bestowed upon Lord

Selkirk for the nominal sum of ten shillings had made him the greatest

individual land-owner in Christendom. His new possession was quite as large as

the province of Egypt in the days of Caesar Augustus. But in some other respects

Lord Selkirk's heritage was much greater. The province of Egypt, the granary of

Rome, was fertile only along the banks of the Nile. More than three-fourths of

Lord Selkirk's domain, on the other hand, was highly fertile soil.

Footnotes:

1. It will be understood that the boundary-line between British

and American territory in the North-West was not yet established. What

afterwards became United States soil v/as at this time claimed by the Hudson's

Bay Company under its charter.

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

The Red River Colony, A Chronicle of the

Beginnings of Manitoba, By Louis Aubrey Wood, Toronto, Glasgow,

Brook & Company 1915

Chronicles of Canada |