Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

The Outlaw Hunters

Chirikoff's crew on the St Paul had long since

returned in safety to Kamchatka, and the garrison of the fort on

Avacha Bay had given up Bering's men as lost forever, when one

August morning the sentinel on guard along the shore front of

Petropavlovsk descried a strange apparition approaching across the

silver surface of an unruffled sea. It was like a huge whale,

racing, galloping, coming in leaps and bounds of flying fins over

the water towards the fort. The soldier telescoped his eyes with his

hands and looked again. This was no whale. There was a mast pole

with a limp skinthing for sail. It was a big, clumsy, raft shaped

flatboat. The oarsmen were rowing like pursued maniacs, rising and

falling bodily as they pulled. It was this that gave the craft the

appearance of galloping over the water. The soldier called down

others to look. Someone ran for the commander of the fort. What

puzzled the onlookers was the appearance of the rowers. They did not

look like human beings; their hair was long; their beards were

unkempt. They were literally naked except for breechclouts and

shoulder pieces of fur. Then somebody shouted the unexpected tidings

that they were the castaways of Bering's crew.

Bugles rang; the fort drum rumbled a muster; the chapel bells pealed

forth; and the whole population of the fort rushed to the waterside

- shouting, gesticulating, laughing, crying - and welcomed with wild

embraces the returning castaways. And while men looked for this one

and that among the two score coming ashore from the raft, and women

wept for those they did not find, on the outskirts of the crowd

stood silent observers - Chinese traders and peddlers from

Manchuria, who yearly visited Kamchatka to gather pelts for the

annual great fur fairs held in China. The Chinese merchants looked

hard; then nodded knowingly to each other, and came furtively down

amid the groups along the shore front and timidly fingered the

matted pelts worn by the half naked men. It was incredible. Each

penniless castaway was wearing the fur of the sea otter, or what the

Russians called the sea beaver, more valuable than seal, and, even

at that day, rarer than silver fox. Never suspecting their value,

the castaways had brought back a great number of the pelts of these

animals; and when the Chinese merchants paid over the value of these

furs in gold, the Russians awakened to a realization that while

Bering had not found a Gamaland, he might have stumbled on as great

a source of wealth as the furs of French Canada or the gold lined

temples of Peru.

The story Bering's men told was that, while searching ravenously

for food on the barren island where they had been cast, they had found vast kelp

beds and seaweed marshes, where pastured the great manatee known as the sea cow.

Its flesh had saved their lives. While hunting the sea cow in the kelp beds and

sea marshes the men had noticed that whenever a swashing sea or tide drove the

shattering spray up the rocks, there would come riding in on the storm whole

herds of another sea denizen - thousands upon thousands of them, so tame that

they did not know the fear of man, burying their heads in the sea kelp while the

storm raged, lifting them only to breathe at intervals. This creature was six

feet long from the tip of its round, cat shaped nose to the end of its stumpy,

beaver shaped tail, with fur the color of ebony on the surface, soft seal color

and grey below, and deep as sable. Quite unconscious of the worth of the fur,

the castaway sailors fell on these visitors to the kelp beds and clubbed right

and left, for skins to protect their nakedness from the biting winter winds.

It was the news of the sea wealth brought to Kamchatka by Bering's men that sent

traders scurrying to the Aleutian Islands and Alaskan shores. Henceforth

Siberian merchants were to vie with each other in outfitting hunters -

criminals, political exiles, refugees, destitute sailors - to scour the coasts

of America for sea otter. Throughout the long line of the Aleutian Islands and

the neighboring coasts of North America, for over a century, hunters' boats -

little cockleshell skiffs made of oiled walrus skin stretched on whalebone

frames, narrow as a canoe, light as cork - rode the wildest seas in the wildest

storms in pursuit of the sea otter. Sea otter became to the Pacific coast what

beaver was to the Atlantic - the magnet that drew traders to the northwest seas,

and ultimately led to the settlement of the northwest coast.

It was, to be sure, dangerous work hunting in wild northern gales on rocks

slippery with ice and through spray that wiped out every outline of precipice

edge or reef; but it offered variety to exiles in Siberia; and it offered more -

a chance of wealth if they survived. Iron for bolts of boats must be brought all

the way from Europe; so the outlaw hunters did without iron, and fastened planks

together as best they could with deer thongs in place of nails, and moss and

tallow in place of tar. In the crazy vessels so constructed they ventured out

from Kamchatka two thousand miles across unknown boisterous seas. Once they had

reached the Aleutians, natives were engaged to do the actual hunting under their

direction. Exiles and criminals could not be expected to use gentle methods to

attain their ends. 'God is high in the heavens and the Czar is far away, 'they

said. The object was quick profit, and plundering was the easiest way to attain

it. How were the Aleutian Indians paid? At first they were not paid at all. They

were drugged into service with vodka, a liquor that put them in a frenzy; and

bayoneted and bludgeoned into obedience. These methods failing, wives and

children were seized by the Russians and held in camp as hostages to guarantee a

big hunt. The Aleuts' one object in meeting the Russian hunter at all was to get

possession of firearms. From the time Bering's crew and Chirikoff's men had

first fired rifles in the presence of these poor savages of the North, the

Indians had realized that ' the stick that thundered ' was a weapon they must

possess, or see their tribe exterminated.

The brigades of sea otter hunters far exceeded in size and wild daring the

platoons of beaver hunters, who ranged by packhorse and canoe from Hudson Bay to

the Rocky Mountains. The Russian ship, provisioned for two or three years, would

moor and draw up ashore for the winter on one of the eleven hundred Aleutian

Islands. Huts would be constructed of driftwood, roofed with sea moss; and as

time went on even rude forts were erected on two or three of the islands - like

Oonalaska or Kadiak - where the kelp beds were extensive and the hunting was

good enough to last for several years. The Indians would then be attracted to

the camp by presents of brandy and glass beads and gay trinkets and firearms.

Perhaps one thousand Aleut hunters would be assembled. Two types of hunting

boats were used - the big 'bidarkie,' carrying twenty or thirty men, and the

little kayak, a mere cockleshell. Oiled walrus skin, stretched taut as a

drumhead, served as a covering for the kayak against the seas, a manhole being

left in the centre for the paddler to ensconce himself waist deep, with oilskin

round his waist to keep the water out. Clothing was worn fur side in, oiled side

out; and the soles of all moccasins were padded with moss to protect the feet

from the sharp rocks. Armed with clubs, spears, steel gaffs and rifles, the

hunters would paddle out into the storm. There were three types of hunting -

long distance rifle shooting, which the Russians taught the Aleuts; still

hunting in a calm sea; storm hunting on the kelp beds and rocks as the wild tide

rode in with its myriad swimmers. Rifles could be used only when the wind was

away from the sea otter beds and the rocks offered good hiding above the sea

swamps. This method was sea otter hunting deluxe. Still hunting could only be

followed when the sea was smooth as glass. The Russian schooner would launch out

a brigade of cockleshell kayaks on an unruffled stretch of sea, which the sea

otter traversed going to and from the kelp beds. While the sea otter is a marine

denizen, it must come up to breathe; and if it does not come up frequently of

its own volition, the gases forming in its body bring it to the surface. The

little kayaks would circle out silent as shadows over the silver surface of the

sea. A round head would bob up, or a bubble show where a swimmer was moving

below the surface. The kayaks would narrow their surrounding circle. Presently a

head would appear. The hunter nearest would deal the death stroke with his steel

gaff, and the quarry would be drawn in. But it was in the storm hunt over the

kelp beds that the wildest work went on. Through the fiercest storm scudded

bidarkies and kayaks, meeting the herds of sea otter as they drove before the

gale. To be sure, the bidarkies filled and foundered; the kayaks were ripped on

the teeth of the rock reefs. But the sea took no account of its dead; neither

did the Russians. Only the Aleut women and children wept for the loss of the

hunters who never returned; and sea otter hunting decreased the population of

the Aleutian Islands by thousands. It was as fatal to the Indian as to the sea

otter. Two hundred thousand sea otters were taken by the Russians in half a

century. Kadiak yielded as many as 6000 pelts in a single year; Oonalaska, 3000;

the Pribylovs, 5000; Sitka used to yield 15,000 a year. Today there are barely

200 a year found from the Commander Islands to Sitka, It may be imagined that

Russian criminals were not easy masters to the simple Aleut women and children

who were held as hostages in camp to guarantee a good hunt. Brandy flowed like

water, the Czar was far away, and it was a land with no law but force. The

Russian hunters cast conscience and fear to the winds. Who could know? God did

not seem to see; and it was two thousand miles to the home fort in Kamchatka.

When the hunt was poor, children were brained with clubbed rifles, women knouted

to death before the eyes of husbands and fathers. In 1745 a whole village of

Aleuts had poison put in their food by the Russians. The men were to eat first,

and when they perished the women and children would be left as slaves to the

Russians. A Cossack, Pushkareff, brought a ship out for the merchant Betshevin

in 1762, and, in punishment for the murder of several brutal members of the crew

by the Aleuts, he kidnapped twenty-five of their women. Then, as storm drove him

towards Kamchatka, he feared to enter the home port with such a damning human

cargo. So he promptly marooned fourteen victims on a rocky coast, and binding

the others hand and foot, threw them into the sea. The merchant and the Cossack

were both finally punished by the Russian government for the crimes of this

voyage; but this did not silence the blood of the murdered women crying to

Heaven for vengeance. In September 1762 the criminal ship came back to Avacha

Bay. In complete ignorance of the Cossack's diabolical conduct, four Russian

ships sailed that very month for the Aleutian Islands. Since 1741, when Bering's

sailors had found the kelp beds, Aleuts had hunted the sea otter and Russians

had hunted the Aleuts. For three years fate reversed the wheel. It was to be a

manhunt of fugitive Russians.

Just before the snow fell in the autumn of 1763 Alexis Drusenin anchored his

ship on the northeast corner of Oonalaska, where the rocks sprawl out in the sea

in five great spurs like the fingers of a hand. The spurs are separated by

tempestuous reef-ribbed seas. The Indians were so very friendly that they

voluntarily placed hostages of good conduct in the Russians' hands. Two or three

thousand Aleut hunters came flocking over the sea in their kayaks to join the

sea otter brigades. On the spur opposite to Drusenin 's anchorage stood an Aleut

village of forty houses; on the next spur, ten miles away across the sea, was

another village of seventy people. The Russian captain divided his crew, and

placed from nine to twelve men in each of the villages. With ample firearms and

enough brandy half a dozen Russians could control a thousand Aleuts. Swaggering

and bullying and loud voiced and pot-valiant, Drusenin and two Cossacks stooped

to enter a low thatched Aleut hut. The entrance step pitched down into a sort of

pit; and as Drusenin stumbled in face foremost a cudgel clubbed down on his

skull.

The Cossack behind stumbled headlong over the prostrate

form of his officer; and in the dark there was a flash of long knives - such

knives as the hunters used in skinning their prey. Both bodies were cut to

fragments. The third man seized an axe as the murderers crowded round him and

beat them back; he then sought safety in flight. There was a hiss of hurtling

spears thrown after him with terrible deftness. With his back pierced in a dozen

places, drenched in his own blood, the Cossack almost tumbled over the prostrate

body of a sentinel who had been on guard at a house down by the ship, and had

been wounded by the flying spears. A sailor dashed out, a yard long bear knife

in his grasp, and dragged the two men inside. Of the dozen Russians stationed

here only four survived; and their hut was beset by a rabble of Aleuts drunk

with vodka, drunk with blood, drunk with a frenzy of revenge.

Cooped up in the hut, the Russians kept guard by twos till nightfall, when,

dragging a bidarkie down to the water, they loaded it with provisions and

firearms, and pushed out in the dark to the moan and heave of an unquiet sea.

Though weakened from loss of blood, the fugitives rowed with fury for the next

spur of rock, ten miles away, where they hoped to find help. The tiderip came

out of the north with angry threat and broke against the rocks, but no blink of

light shone through the dark from the Russian huts ashore. The men were afraid

to land, and afraid not to land. Wind and sea would presently crush their frail

craft to kindling wood against the rocky shore.

The Russians sprang out, waded ashore, uttered a shout! Instantly lances and

spears fell about them like rain. They joined hands and ran for the cove where

the big schooner had been moored. Breathlessly they waited for the dawn to

discover where their ship lay; but daylight revealed only the broken wreckage of

the vessel along the shore, while all about were bloodstains and pieces of

clothing and mutilated bodies, which told but too plainly that the crew had been

hacked to pieces. There was not a moment to be lost. Before the mist could lift,

the fugitives gathered up some provisions scattered on the shore and ran for

their lives to the high mountains farther inland. And when daylight came they

scooped a hole in the sand, drew a piece of sailcloth over this, and lay in

hiding till night.

From early December to early February the Russians hid in the

caves of the Oonalaska Mountains. Clams, shellfish, seabirds stayed their

hunger. It is supposed that they must have found shelter in one of the caves

where there are medicinal hot springs; otherwise, they would have perished of

cold. In February they succeeded in making a rude boat, and in this they set out

by night to seek the ships of other Russian hunters. For a week they rowed out

only at night. Then they began to row by day. They were seen by Indians, and

once more sought safety in the caves of the mountains, where they remained in

hiding for five weeks, venturing out only at night in search of food. Here, snow

water and shellfish were all they had to sustain them; and again they must build

a rude raft to escape. Towards the end of March they descried a Russian vessel

in the offing, and at last succeeded in reaching friends.

Almost the same story could be told of the crews of each of the ships that had

sailed from Avacha Bay in September 1762. One ship foundered. The castaways were

stabbed where they lay in exhausted sleep. Every member of the crew on a third

ship had been slain round a bathhouse, such as Russian hunters built in that

climate to enable them to ward off rheumatism by vapor plunges. One ship only

escaped the general butchery and carried the refugees home.

Of course, Cossack and hunter exacted terrible vengeance for this massacre.

Whole villages were burned to the ground and every inhabitant sabred. On one

occasion, as many as three hundred victims were tied in line and shot. The

result was that the Cossacks' outrages and the Aleuts' vengeance drew the

attention of the Russian government to this lucrative fur trade in the far new

land. The disorders put an end to free, unrestricted trade.

Henceforth a hunter must have a license; and a license implied the favor of the

court. The court saw to it that a governor took up his residence in the region

to enforce justice and to compel the hunters to make honest returns. Like the

Hudson's Bay men, the Russian fur traders had to report direct to the crown.

Thus was inaugurated on the west coast of America the Russian regime, which

ended only in 1867, when Alaska was ceded to the United States.

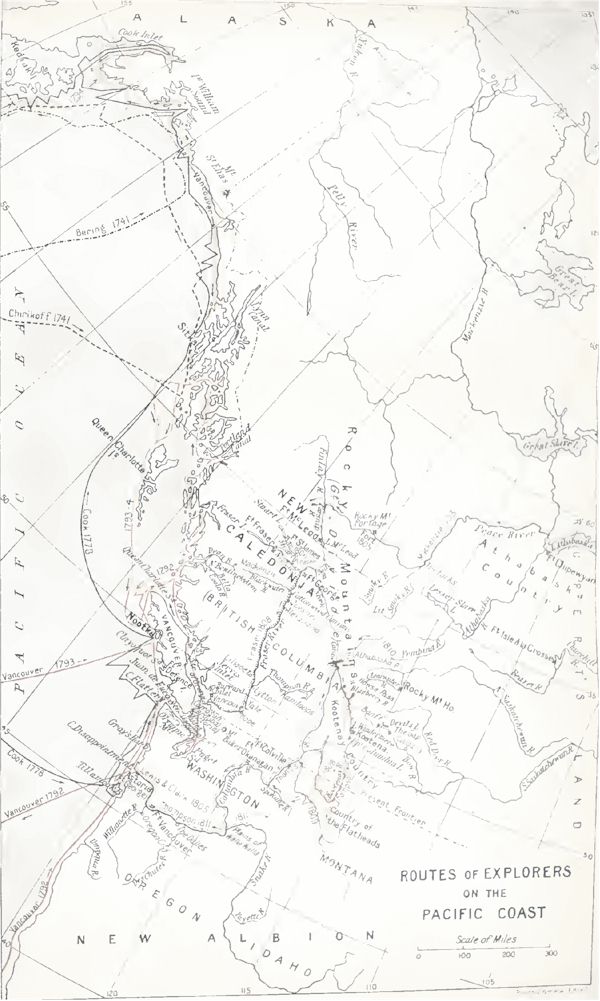

Routes of Explorers on the Pacific Coast

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

Pioneers of the Pacific Coast, A Chronicle Of Sea

Rovers And Fur Hunters, By Agnes C. Laut, Toronto. Glasgow, Brook &

Company, 1915

Chronicles of Canada |