Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

Mackenzie Descends the Great River of the

North

The next great landmark in the exploration of the

Far North is the famous voyage of Alexander Mackenzie down the river

which bears his name, and which he traced to its outlet into the

Arctic Ocean. This was in 1789. By that time the Pacific coast of

America and the coast of Siberia over against it had already been

explored. Even before Hearne's journey the Danish navigator Bering,

sailing in the employ of the Russian government, had discovered the

strait which separates Asia from America, and which commemorates his

name. Four years after Hearne's return (1776) the famous navigator

Captain Cook had explored the whole range of the American coast to

the north of what is now British Columbia, had passed Bering Strait

and had sailed along the Arctic coast as far as Icy Cape. The

general outline of the north of the continent

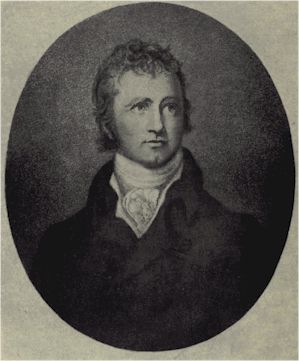

Sir Alexander Mackenzie

From a painting by Lawrence

of America, and at any rate the vast distance to be traversed to

reach the Pacific from the Atlantic, could now be surmised with some accuracy.

But the internal geography of the continent still contained an unsolved mystery.

It was known that vast bodies of fresh water far beyond the basin of the

Saskatchewan and the Columbia emptied to-wards the north. Hearne had revealed

the existence of the Great Slave Lake, and the advance of daring fur traders

into the north had brought some knowledge of the great stream called the Peace,

which rises far in the mountains of the west, and joins its waters to Lake

Athabaska. It was known that this river after issuing from the Athabaska Lake

moved onwards, as a new river, in a vast flood to-wards the north, carrying with

it the tribute of uncounted streams. These rivers did not flow into the Pacific.

Nor could so great a volume of water make its way to the sea through the shallow

torrent of the Coppermine or the rivers that flowed north-eastward over the

barren grounds. There must exist somewhere a mighty river of the north running

to the frozen seas.

It fell to the lot of Alexander Mackenzie to find the solution of this problem.

The circumstances which led to his famous journey arose out of the progress of

the fur trade and its extension into the Far West. The British possession of

Canada in 1760 had created a new situation. The monopoly enjoyed by the Hudson's

Bay Company was rudely disturbed. Enterprising British traders from Montreal,

passing up the Great Lakes, made their way to the valley of the Saskatchewan

and, whether legally or not, contrived to obtain an increasing share of the furs

brought from the interior. These traders were at first divided into

partner-ships and small groups, but presently, for the sake of co-operation and

joint defense, they combined (1787) into the powerful body known as the North-

West Company, which from now on entered into desperate competition with the

great corporation that had first occupied the field. The Hudson's Bay Company

and its rival sought to carry their operations as far inland as possible in

order to tap the supplies at their source. They penetrated the valleys of the

Assiniboine, the Red, and the Saskatchewan Rivers, and founded, among others,

the forts which were destined to become the present cities of Winnipeg, Brandon,

and Edmonton. The annals of North- West Canada during the next thirty-three

years are made up of the recital of the commercial rivalry, and at times the

actual conflict under arms, of the two great trading companies.

It was in the service of the North-West Company that Alexander Mackenzie made

his famous journey. He had arrived in Canada in 1779. After five years spent in

the counting-house of a trading company at Montreal, he had been assigned for a

year to a post at Detroit, and in 1785 had been elevated to the dignity of a

bourgeois or partner in the North-West Company. In this capacity Alexander

Mackenzie was sent out to the Athabaska district to take control, in that vast

and scarcely known region, of the posts of the traders now united into the

North-West Company.

A glance at the map of Canada will show the commanding geographical position

occupied by Lake Athabaska, in a country where the water-ways formed the only

means of communication. It receives from the south and west the great streams of

the Athabaska and the Peace, which thus connect it with the prairies of the

Saskatchewan valley and with the Rocky Mountains. Eastward a chain of lakes and

rivers connects it and the forest country which lies about it with the barren

grounds and the forts on Hudson Bay, while to the north, issuing from Lake

Athabaska, a great and unknown river led into the forests, moving towards an

unknown sea.

It was Mackenzie's first intention to make Lake Athabaska the frontier of the

operations of his company. Acting under his instructions, his cousin Roderick

Mackenzie, who served with him, selected a fine site on a cape on the south side

of the lake and erected the post that was named Fort Chipewyan. Beautifully

situated, with good timber and splendid fisheries and easy communication in all

directions, the fort rapidly became the central point of trade and travel in the

far north-west. But it was hardly founded before Mackenzie had already conceived

a wider scheme. Chipewyan should be the emporium but not the outpost of the fur

trade; using it as a base, he would descend the great unknown water-way which

led north, and thus bring into the sphere of the company's operations the whole

region between Lake Athabaska and the northern sea. Alexander Mackenzie's object

was, in name at least, commercial the extension of the trade of the North-West

Company. But in reality, his incentive was that instinctive desire to widen the

bounds of geographical knowledge, and to roll back the mystery of unknown lands

and seas which had already raised Hearne to eminence, and which later on was to

lead Franklin to his glorious disaster.

It was on Wednesday, June 3, 1789, that Alexander Mackenzie's little flotilla of

four birch - bark canoes set out across Lake Athabaska on its way to the north.

In Mackenzie's canoe were four French-Canadian voyageurs, two of them

accompanied by their wives, and a German. Two other canoes were filled with

Indians, who were to act as guides and interpreters. At their head was a notable

brave who had been one of the band of Matonabbee, Hearne's famous guide. From

his frequent visits to the English post at Fort Churchill he had acquired the

name of the ' English Chief.' Another canoe was in charge of Leroux, a

French-Canadian in the service of the company, who had already descended the

Slave River, as far as the Great Slave Lake. Leroux and his men carried trading

goods and supplies.

The first part of the journey was by a route already known. The

voyageurs paddled across the twenty miles of water which here forms the breadth

of Lake Athabaska, entered a river running from the lake, and followed its

winding stream. They encamped at night seven miles from the lake. The next

morning at four o' clock the canoes were on their way again, descending the

winding river through a low forest of birch and willow. After a paddle of ten

miles, a bend in the little river brought the canoes out upon the broad stream

of the Peace River, its waters here being upwards of a mile wide and running

with a strong current to the north. On our modern maps this great stream after

it leaves Lake Athabaska is called the Slave river: but it is really one and the

same mighty river, carrying its waters from the valleys of British Columbia

through the gorges of the Rocky Mountains, passing into the Great Slave Lake,

and then, under the name of the Mackenzie, emptying into the Arctic.

In the next five days Mackenzie's canoes successfully descended the river to the

Great Slave Lake, a distance of some two hundred and thirty-five miles. The

journey was not without its dangers. The Slave River has a varied course: at

times it broadens out into a great sheet of water six miles across, flowing with

a gentle current and carrying the light canoes gently upon its unruffled

surface. In other places it is confined into a narrow channel, breaks into swift

eddies and pours in boiling rapids over the jagged rocks. Over the upper rapids

of the river, Mackenzie and his men were able to run their canoes fully laden;

but lower down were long and arduous portages, rendered dangerous by the masses

of broken ice still clinging to the banks of the river. As they neared the Great

Slave Lake boisterous gales from the north-east lashed the surface of the river

into foam and brought violent showers of rain. But the voyageurs were trained

men, accustomed to face the dangers of northern navigation.

A week of travel brought them on June 9 to the Great Slave Lake.

It was still early in the season. The rigor of winter was not yet relaxed. As

far as the eye could see the surface of the lake presented an unbroken sheet of

ice. Only along the shore had narrow lanes of open water appeared. The weather

was bitterly cold, and there was no immediate prospect of the break-up of the

ice.

For a fortnight Mackenzie and his party remained at the lake, skirting its

shores as best they could, and searching among the bays and islands of its

western end for the outlet towards the north which they knew must exist. Heavy

rain, alternating with bitter cold, caused them much hardship. At times it froze

so hard that a thin sheet of new ice covered even the open water of the lake.

But as the month advanced the mass of old ice began slowly to break; strong

winds drove it towards the north, and the canoes were presently able to pass,

with great danger and difficulty, among the broken floes. Mackenzie met a band

of Yellow Knife Indians, who assured him that a great river ran out of the west

end of the lake, and offered a guide to aid him in finding the channel among the

islands and sandbars of the lake. Convinced that his search would be successful,

Mackenzie took all the remaining supplies into his canoes and sent back Leroux

to Chipewyan with the news that he had g9ne north down the great river. But even

after obtaining his guide Mackenzie spent four days searching for the outlet It

was not till the end of the month of June that his search was rewarded, and, at

the extreme south-west, the lake, after stretching out among islands and

shallows, was found to contract into the channel of a river.

The first day of July saw Mackenzie's canoes floating down the stream that bears

his name. From now on, progress became easier. At this latitude and season the

northern day gave the voyageurs twenty hours of sunlight in each day, and with

smooth water and a favoring current the descent was rapid. Five days after

leaving the Great Slave Lake the canoes reached the region where the waters of

the Great Bear Lake, then still unknown, drain into the Mackenzie. The Indians

of this district seemed entirely different from those known at the trading

posts. At the sight of the canoes and the equipment of the voyageurs they made

off and hid among the rocks and trees beside the river. Mackenzie's Indians

contrived to make themselves understood, by calling out to them in the Chipewyan

language, but the strange Indians showed the greatest reluctance and

apprehension, and only with difficulty allowed Mackenzie's people to come among

them. Mackenzie notes the peculiar fact that they seemed unacquainted with

tobacco, and that even fire-water was accepted by them rather from fear of

offending than from any inclination. Knives, hatchets and tools, how-ever, they

took with great eagerness. On learning of Mackenzie's design to go on towards

the north they endeavored with every possible expression of horror to induce him

to turn back. The sea, they said, was so far away that winter after winter must

pass before Mackenzie could hope to reach it: he would be an old man before he

could complete the voyage. More than this, the river, so they averred, fell over

great cataracts which no one could pass; he would find no animals and no food

for his men. The whole country was haunted by monsters. Mackenzie was not to be

deterred by such childish and obviously interested terrors. His interpreters

explained that he had no fear of the horrors that they depicted, and, by a heavy

bribe, consisting of a kettle, an axe, and a knife, he succeeded in enlisting

the services of one of the Indians as a guide. That the terror of the Far North

professed by these Indians or at any rate the terror of going there in strange

company, was not wholly imaginary was made plain from the conduct of the guide.

When the time came to depart he showed every sign of anxiety and fear: he sought

in vain to induce his friends to take his place: finding that he must go, he

reluctantly bade farewell to his wife and children, cutting off a lock of his

hair and dividing it into three parts, which he fastened to the hair of each of

them.

On July 5, the party set out with their new guide, and on the same afternoon

passed the mouth of the Great Bear river, which joins the Mackenzie in a flood

of sea-green water, fresh, but colored like that of the ocean. Below this point,

they passed many islands. The banks of the river rose to high mountains covered

with snow. The country, so the guide said, was here filled with bears, but the

voyageurs saw nothing worse than mosquitoes, which descended in clouds upon the

canoes. As the party went on to the north, the guide seemed more and more

stricken with fear and consumed with the longing to return to his people. In the

morning after breaking camp nothing but force would induce him to embark, and on

the fourth night, during the confusion of a violent thunder-storm, he made off

and was seen no more.

The next day, however, Mackenzie supplied his place, this time by force, from a

band of roving Indians. The new guide told him that the sea was not far away,

and that it could be reached in ten days. As the journey continued the river was

broken into so many channels and so dotted with islands, that it was almost

impossible to decide which was the main water-way. The guide's advice was

evidently influenced by his desire to avoid the Eskimos, and, like his

predecessor, to keep away from the supposed terrors of the North. The shores of

the river were now at times low, though usually lofty mountains could be seen

about ten miles away. Trees were still present, especially fir and birch, though

in places both shores of the river were entirely bare, and the islands were mere

banks of sand and mud to which great masses of ice adhered. An observation taken

on July 10 showed that the voyageurs had reached latitude 67° 47' north. From

the extreme variation of the compass, and from other signs, Mackenzie was now

certain* that he was approaching the northern ocean. He was assured that in a

few days more of travel he could reach its shores. But in the meantime his

provisions were running low. His Indian guide, a prey to fantastic terrors,

endeavored to dissuade him from his purpose, while his canoe men, now far beyond

the utmost limits of the country known to the fur trade, began to share the

apprehensions of the guide, and clamored eagerly for return. Mackenzie him-self

was of the opinion that it would not be possible for him to return to Chipewyan

while the rivers were still open, and that the approach of winter must surprise

him in these northern solitudes. But in spite of this he could not bring himself

to turn back. With his men he stipulated for seven days; if the northern ocean

were not found in that time he would turn south again.

The expedition went forward. On July 10, they made a course of thirty-two miles,

the river sweeping with a strong current through a low, flat country, a mountain

range still visible in the west and reaching out towards the north. At the spot

where they pitched their tents at night on the river bank they could see the

traces of an encampment of Eskimos. The sun shone brilliantly the whole night,

never descending below the horizon. Mackenzie sat up all night observing its

course in the sky. At a quarter to four in the morning, the canoes were off

again, the river winding and turning in its course but heading for the

north-west. Here and there on the banks they saw traces of the Eskimos, the

marks of camp fires, and the remains of huts, made of drift-wood covered with

grass and willows. This day the canoes travelled fifty-four miles. The prospect

about the travelers was gloomy and dispiriting. The low banks of the river were

now almost tree-less, except that here and there grew stunted willow, not more

than three feet in height. The weather was cloudy and raw, with gusts of rain at

intervals. The discontent of Mackenzie's companions grew apace: the guide was

evidently at the end of his knowledge; while the violent rain, the biting cold

and the fear of an attack by hostile savages kept the voyageurs in a continual

state of apprehension. July 12 was marked by continued cold, and the canoes

traversed a country so bare and naked that scarcely a shrub could be seen. At

one place the land rose in high banks above the river, and was bright with short

grass and flowers, though all the lower shore was now thick with ice and snow,

and even in the warmer spots the soil was only thawed to a depth of four inches.

Here also were seen more Eskimo huts, with fragments of sledges, a square stone

kettle, and other utensils lying about.

Mackenzie was now at the very delta of the great river, where it discharges its

waters, broken into numerous and intricate channels, into the Arctic ocean. On

Sunday, July 12, the party encamped on an island that rose to a considerable

eminence among the flat and dreary waste of broken land and ice in which the

travelers now found themselves. The channels of the river had here widened into

great sheets of water, so shallow that for stretches of many miles, east and

west, the depth never exceeded five feet. Mackenzie and ' English Chief,' his

principal follower, ascended to the highest ground on the island, from which

they were able to command a wide view in all directions. To the south of them

lay the tortuous and complicated channels of the broad river which they had

descended; east and north were islands in great number; but on the westward side

the eye could discern the broad field of solid ice that marked the Arctic Ocean.

Mackenzie had reached the goal of his endeavors. His followers, when they

learned that the open sea, the mer d'ouest as they called it, was in sight, were

transformed; instead of sullen ill-will they manifested the highest degree of

confidence and eager expectation. They declared their readiness to follow their

leader wherever he wished to go, and begged that he would not turn back with-out

actually reaching the shore of the unknown sea. But in reality they had already

reached it. That evening, when their camp was pitched and they were about to

retire to sleep, under the full light of the unsinking sun, the inrush of the

Arctic tide, threatening to swamp their baggage and drown out their tents,

proved beyond all doubt that they were now actually on the shore of the ocean.

For three days Mackenzie remained beside the Arctic Ocean. Heavy

gales blew in from the northwest, and in the open water to the westward whales

were seen. Mackenzie and his men, in their exultation at this final proof of

their whereabouts, were rash enough to start in pursuit in a canoe. Fortunately,

a thick curtain of fog fell on the ocean and terminated the chase. In memory of

the occurrence, Mackenzie called his island Whale Island. On the morning of July

14, 1789, Mackenzie, convinced that his search had succeeded, ordered a post to

be erected on the island beside his tents, on which he carved the latitude as he

had calculated it (69° 14' north), his own name, the number of persons who were

with him and the time that was spent there.

This day Mackenzie spent in camp, for a great gale, blowing with rain and bitter

cold, made it hazardous to embark. But on the next morning the canoes were

headed for the south, and the return journey was begun. It was time indeed. Only

about five hundred pounds weight of supplies was now left in the canoes enough,

it was calculated, to suffice for about twelve days. As the return journey might

well occupy as many weeks, the fate of the voyageurs must now depend on the

chances of fishing and the chase.

As a matter of fact the ascent of the river, which Mackenzie conducted with

signal success and almost without incident, occupied two months. The weather was

favorable. The wild gales which had been faced in the Arctic delta were left

behind, and, under mild skies and unending sunlight, and with wild fowl abundant

about them, the canoes were urged steadily against the stream. The end of the

month of July brought the explorers to the Great Bear River; from this point an

abundance of berries on the banks of the stream the huckleberry, the raspberry

and the saskatoon afforded a welcome addition to their supplies. As they reached

the narrower parts of the river, where it flowed between high banks, the swift

current made paddling useless and compelled the men to haul the canoes with the

towing line. At other times steady strong winds from the north enabled them to

rig their sails and skim with-out effort over the broad surface of the river.

Mackenzie noted with interest the varied nature and the fine resources of the

country of the upper river. At one place petroleum, having the appearance of

yellow wax, was seen oozing from the rocks; at another place a vast seam of coal

in the river bank was observed to be burning. On August 22 the canoes were

driven over the last reaches of the Mackenzie with a west wind strong and cold

behind them, and were carried out upon the broad bosom of the Great Slave Lake.

The voyageurs were once more in known country. The navigation of the lake, now

free from ice, was without difficulty, and the canoes drove at a furious rate

over its waters. On August 24 three canoes were sighted sailing on the lake, and

were presently found to contain Leroux and his party, who had been carrying on

the fur trade in that district during Mackenzie's absence.

The rest of the journey offered no difficulty. There remained, indeed, some two

hundred and sixty miles of paddle and portage to traverse the Slave River and

reach Fort Chipewyan. But to the stout arms of Mackenzie's trained voyageurs

this was only a summer diversion. On September 12, 1789, Alexander Mackenzie

safely reached the fort. His voyage had occupied one hundred and two days. Its

successful completion brought to the world its first knowledge of that vast

waterway of the northern country, whose extensive resources in timber and coal,

in mineral and animal wealth, still await development.

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

Adventurers of the Far North, Pioneers of the

North and West, By Stephen Leacock, Hunter-Rose Co., Limited,

Toronto

Chronicles of Canada |