Canadian

Research

Alberta

British

Columbia

Manitoba

New Brunswick

Newfoundland

Northern

Territories

Nova Scotia

Nunavut

Ontario

Prince Edward

Island

Quebec

Saskatchewan

Yukon

Canadian Indian

Tribes

Chronicles of

Canada

Free Genealogy Forms

Family Tree

Chart

Research

Calendar

Research Extract

Free Census

Forms

Correspondence Record

Family Group Chart

Source

Summary New Genealogy Data

Family Tree Search

Biographies

Genealogy Books For Sale

Indian Mythology

US Genealogy

Other Websites

British Isles Genealogy

Australian Genealogy

FREE Web Site Hosting at

Canadian Genealogy

|

Across the Plains

For several years La Vérendrye had been hearing

wonderful accounts of a tribe of Indians in the West who were known

as the Mandans. Wherever he went, among the Chippewas, the Crees, or

the Assiniboines, some one was sure to speak of the Mandans, and the

stories grew more and more marvelous. La Vérendrye knew that Indians

were very much inclined to exaggerate. They would never spoil a good

story by limiting it to what they knew to be true. They liked a joke

as well as other people; and, when they found that the white men who

visited them were eager to know all about the country and the tribes

of the far interior, they invented all sorts of impossible stories,

in which truth and fiction were so mingled that at length the

explorers did not know what to believe.

Much that was told him by the Indians concerning the Mandans La

Vérendrye knew could not possibly be true; he thought that some of

their stories were probably correct. The Indians said that the

Mandans were white like himself, that they dressed like Europeans,

wore armor, had horses and cattle, cultivated the ground, and lived

in fortified towns. Their home was described as being far towards

the setting sun, on a great river that flowed into the ocean. La

Vérendrye knew that the Spaniards had made settlements on the

western coast of America, and he thought that the mysterious

strangers might perhaps be Spaniards. At any rate, they seemed to be

white men, and, if the Indian stories were even partially true, they

would be able to show him that way to the great water which it was

the ambition of his life to find. His resolve, therefore, was

inevitable. He would visit these white strangers, whoever they might

be; and he had great hopes that they would be able to guide him to

the object of his quest.

For some time, however, he was not able to carry out this intended

visit to the Mandans. The death of his nephew La Jemeraye, followed

soon after by the murder of his son Jean, upset all his plans for a

time. Further, he had great difficulty in keeping peace among the

Indian tribes. The Chippewas and the Crees, who had always been

friendly to the French, were indignant at the treacherous massacre

of the white men by the Sioux, and urged La Vérendrye to lead a war

party against this enemy. La Vérendrye not only refused to do this

himself, but he told them that they must on no account go to war

with the Sioux. He warned them that their Great Father, the king of

France, would be very angry with them if they disobeyed his

commands. Had they not known him so well, the Indians would have

despised La Vérendrye as a coward for refusing to revenge himself

upon the Sioux for the death of his son; but they knew that,

whatever his reason might be, it was not due to any fear of the

Sioux. As time went on, they thought that he would perhaps change

his mind, and again and again they came to him begging for leave to

take the war-path. 'The blood of your son,' they said, 'cries for

revenge. We have not ceased to weep for him and for the other

Frenchmen who were slain. Give us permission and we will avenge

their death upon the Sioux.'

La Vérendrye, however, disregarding his personal feelings, knew that

it would be fatal to all his plans to let the friendly Indians have

their way. An attack on the Sioux would be the signal for a general

war among all the neighboring tribes. In that case his forts would

be destroyed and the fur trade would be broken up. In the end, he

and his men would probably be driven out of the western country, and

all his schemes for the discovery of the Western Sea would come to

nothing. It was therefore of the utmost importance that he should

remain where he was, in the country about the Lake of the Woods,

until the excitement among the Indians had quieted down and there

was no longer any immediate danger of war.

At length, in the summer of 1738, La Vérendrye felt that he could

carry out his plan of visiting the Mandans. He left one of his sons,

Pierre, in charge of Fort St Charles, and with the other two,

François and Louis, set forth on his journey to the West. Travelling

down the Winnipeg river in canoes, they stopped for a few hours at

Fort Maurepas, then crossed Lake Winnipeg and paddled up the muddy

waters of Red River to the mouth of the Assiniboine, the site of the

present city of Winnipeg, then seen by white men for the first time.

La Vérendrye found it occupied by a band of Crees under two war

chiefs. He landed, pitched his tent on the banks of the Assiniboine,

and sent for the two chiefs and reproached them with what he had

heard—that they had abandoned the French posts and had taken their

furs to the English on Hudson Bay. They replied that the accusation

was false; that they had gone to the English during only one season,

the season in which the French had abandoned Fort Maurepas after the

death of La Jemeraye, and had thus left the Crees with no other

means of getting the goods they required. 'As long as the French

remain on our lands,' they said, 'we promise you not to go elsewhere

with our furs.' One of the chiefs then asked him where he was now

going. La Vérendrye replied that it was his purpose to ascend the

Assiniboine river in order to see the country. 'You will find

yourself among the Assiniboines,' said the chief; 'and they are a

useless people, without intelligence, who do not hunt the beaver,

and clothe themselves only in the skins of buffalo. They are a

good-for-nothing lot of rascals and might do you harm.' But La

Vérendrye had heard such tales before and was not to be frightened

from his purpose. He took leave of the Crees, turned his canoes up

the shallow waters of the Assiniboine river, and ascended it to

where now stands the city of Portage la Prairie. Here he built a

fort, which he named Fort La Reine, in honor of the queen of France.

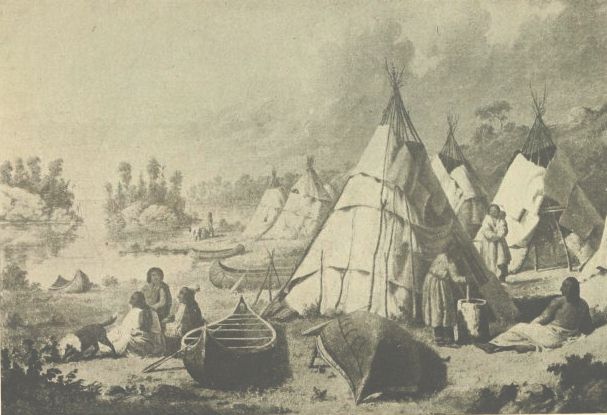

An Indian encampment

From a painting by Paul Kane

While this was being done, a party of Assiniboines arrived. La

Vérendrye soon found, as he had expected, that the Crees through jealousy had

given the Assiniboines a character which they did not deserve. With all

friendliness they welcomed the strangers and were overjoyed at the presents

which the French gave them. The most valued presents consisted of knives,

chisels, awls, and other small tools. Up to this time these people had been

dependent upon implements made of stone and of bone roughly fashioned to serve

their purposes, and these implements were very crude and inferior compared with

the sharp steel tools of the white men.

While La Vérendrye had been occupied in building Fort La Reine, one of his men,

Louvière, had been sent to the mouth of the Assiniboine to put up a small post

for the Crees. He found a suitable place on the south bank of the Assiniboine,

near the point where it enters the Red, and here he built his trading post and

named it Fort Rouge. This fort was abandoned in a year or two, as it was soon

found more convenient to trade with the Indians either at Fort Maurepas near the

mouth of the Winnipeg, or at Fort La Reine on the Assiniboine. The memory of the

fort is, however, preserved to this day. The quarter of Winnipeg in the vicinity

of the old fort is still known as Fort Rouge. The memory of La Vérendrye is also

preserved, for a large school built near the site of the old fort bears the name

of the great explorer.

The completion of Fort La Reine freed La Vérendrye to make preparations for his

journey to the Mandans. He left some of his men at the fort and selected twenty

to accompany him on his expedition. To each of these followers he gave a supply

of powder and bullets, an ax, a kettle, and other things needful by the way. In

later years horses were abundant on the western prairie, but at that time

neither the French nor the Indians had horses, and everything needed for the

journey was carried on men's backs.

Three days after leaving Fort La Reine, La Vérendrye met a party of Assiniboines

travelling over the prairie. He gave them some small presents, and told them

that he had built in their country a fort where they could get all kinds of

useful articles in exchange for their furs and provisions. They seemed delighted

at having white men so near, and promised to keep the fort supplied with

everything that the traders required.

A day or two afterwards several other Indians appeared, from an Assiniboine

village. They bore hospitable messages from the chiefs, who begged the white

travelers to come to visit them. This it was difficult to do. The village was

some miles distant from the road on which they were travelling and already they

had lost much time because their guide was either too lazy or too stupid to take

them by the most direct way to the Mandan villages on the banks of the Missouri.

Still, La Vérendrye did not think it wise to disappoint the Assiniboines, or to

offend them, since he might have to depend upon their support in making his

plans for further discoveries. Accordingly, although it was now nearly the

middle of November, the very best time of the year for travelling across the

plains, he made up his mind to go to the Assiniboine village.

As the party drew near the village, a number of young warriors came to meet

them, and to tell them that the Assiniboines were greatly pleased to have them

as guests. It is possible that the Assiniboines had heard of the presents which

the French had given to some of their countrymen, and that they too hoped to

receive knives, powder and bullets, things which they prized very highly. At any

rate, the explorer and his men received vociferous welcome when they entered the

village. 'Our arrival,' says La Vérendrye, 'was hailed with great joy, and we

were taken into the dwelling of a young chief, where everything had been made

ready for our reception. They gave us and all our men very good cheer, and none

of us lacked appetite.'

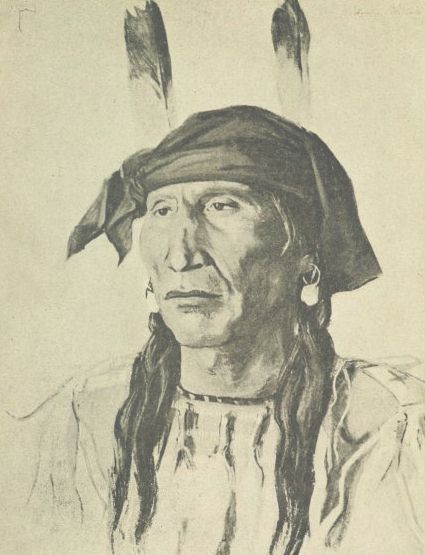

An Assiniboine Indian.

From a pastel by Edmund Morris

The following day La Vérendrye sent for the principal chiefs of the tribe, and

gave to each of them a present of powder and ball, or knives and tobacco. He

told them that if the Assiniboines would hunt beaver diligently and would bring

the skins to Fort La Reine, they should receive in return everything that they

needed. One of the chiefs made a speech in reply. 'We thank you,' he said, 'for

the trouble you have taken to come to visit us. We are going to accompany you to

the Mandans, and then to see you safely back to your fort. We have already sent

word to the Mandans that you are on your way to visit them, and the Mandans are

delighted. We shall travel by easy marches, so that we may hunt by the way and

have plenty of provisions.' The explorer was not wholly pleased to find that the

entire village was to accompany him, for this involved still further delays on

the journey. It was necessary, however, to give no cause of offence; so he

thanked them for their good-will, and merely urged that they should be ready to

leave as soon as possible and travel with all speed by the shortest road, as the

season was growing late.

On the next morning they all set out together, a motley company, the French with

their Indian guides and hunters accompanied by the entire village of

Assiniboines. La Vérendrye was astonished at the orderly way in which these

savages, about six hundred in number, travelled across the prairies. Everything

was done in perfect order, as if they were a regiment of trained soldiers. The

warriors divided themselves into parties; they sent out scouts in advance to

both the right and the left, in order to keep watch for enemies and also to look

out for buffalo and other game; the old men marched in the centre with the women

and the children; and in the rear was a strong guard of warriors. If the scouts

saw buffalo ahead, they signaled to the rear-guard, who crept round the herd on

both sides until it was surrounded. They killed as many buffaloes as were needed

to provision the camp, and this completed the men's part of the work. It was the

women who cut up the meat and carried it to the place where the company encamped

for the night. The women, indeed, were the burden-bearers and had to carry most

of the baggage. There were, of course, dogs in great numbers on such excursions,

and these bore a part of the load. The men burdened themselves with nothing but

their arms.

This site includes some historical materials that

may imply negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of

a particular period or place. These items are presented as part of

the historical record and should not be interpreted to mean that the

WebMasters in any way endorse the stereotypes implied.

Chronicles of Canada, Pathfinders of the Great

Plains, La Vérendrye Explorations, 1731-43, by Lawrence J. Burpee,

1914

Chronicles of Canada |